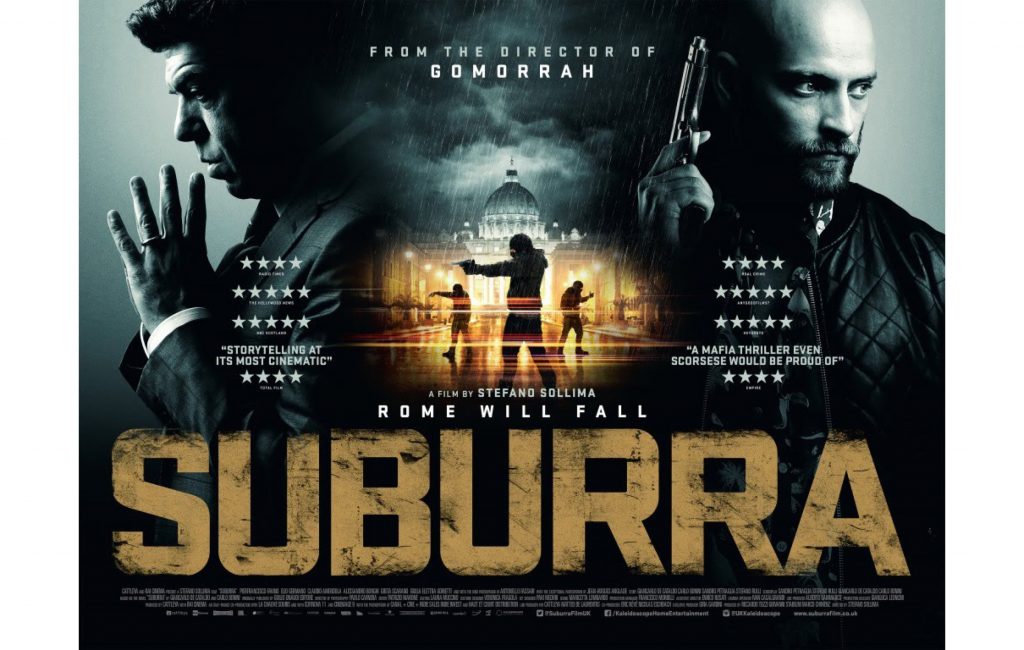

This week I finished watching Suburra, a ten-episode TV series about the Italian Mafia. The series, a spinoff of a movie of homonymous title, piggybacks on the success of another mini-series of the genre. The difference between one and the other is palpable and, although I enjoyed Suburra, I found it to be the light, caffeine-free version of its TV predecessor, Gomorrah.

Initially, I intended to make an observation of how architecture plays a character role in the series Gomorrah. Having now watched Suburra, I find myself making a cinematic comparison between both, going far beyond my intended objective.

The titles of both series are phonetically related, leading me to believe there was a quest for emulation (both are named after movies that preceded them). Both titles allude to location. But there, in the titles, clearly stands the difference. Suburra is named after a lower-class squalor outside of Rome where “not-too-good” things happen. Gomorrah refers to the city of biblical mythology which found its fate through incorrigible misbehaving. One is real and tangible; it can be entered and escaped. The other is mythical; it exists solely in an imagined world.

In Gomorrah, which is now under production for a third season, there are no characters who are redeemable in any way. Everyone is callously perverse – even the architecture, a character in both. While Gomorrah exudes European film grit, Suburra appears to be coated with the naiveté of American film. Undoubtedly due to its American producer Netflix, Suburra is imbued with a puritanism which permeates the production. One big difference is how film locations and architectural settings were chosen by both productions. Besides architecture, both series show their larger settings, the cities, in wide angle. Suburra shows Rome in all its glory. Events take place in front of the Pantheon, along Via Condoti, near the monument to Vittorio Emmanuelle, by the Forum. In Gomorrah, we see Naples in its deepest degeneration. Both series are set by the sea, which also plays a role; soothing in one, menacing in the other.

Both series have distinct cinematography in how shot-framing is carefully studied. Suburra’s frequently-used one-point perspectives and well-behaved symmetry are a counterpoint to Gomorrah’s unruly, asymmetrical views. While Suburra utilizes some strange cinematographic tricks like veiling all scenes involving the gypsy clan in a greenish-yellow hue (reminiscent of Batman’s TV series where scenes shot at the archenemies’ quarters were always tilted as if to convey the crookedness of the actions they portray), Gomorrah is shot with Michael-Mannesque aesthetics, especially the night scenes.

Parallels abound, so a side-by-side comparison is merited.

Generationally, elements in Suburra show the main characters’ progenitor generation as wicked to the core, while the millennials all have a good side. Be it through a struggle to save a mother’s dream or spare an enemy’s dog’s life, fulfilling a father’s desire of moving beyond the limitations of a blue-collar future, or being able to achieve and maintain friendship, we can see a saving factor in each of the three main millennial characters in Suburra. You want the good in each of them to come out; you want to save them. In Gomorrah, only one’s inner-demons can bond with such monstrous personalities.

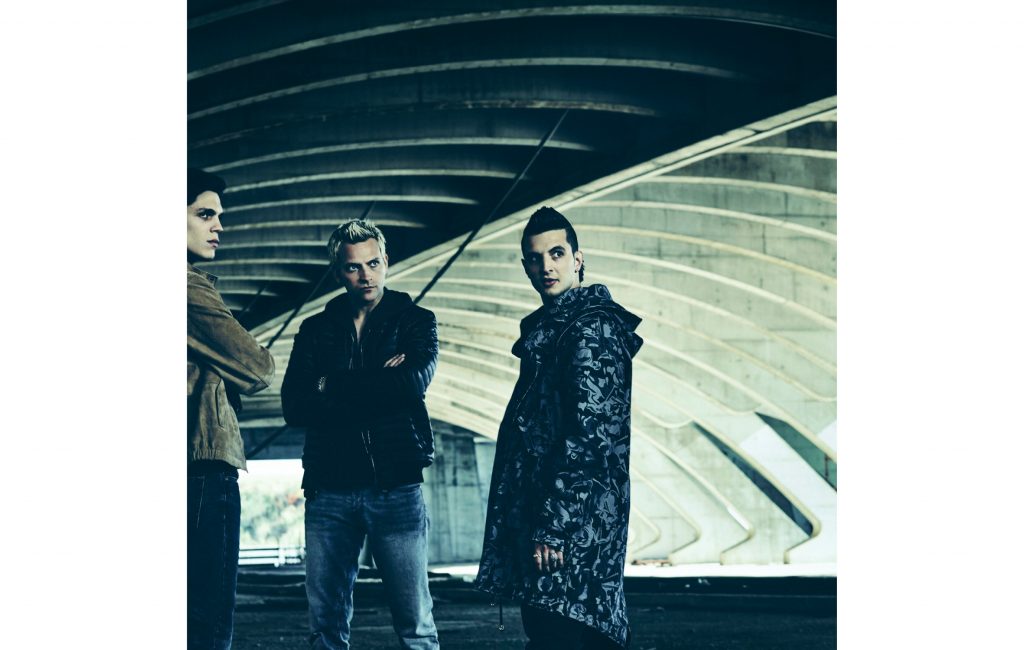

Comparable characters in both series have intrinsically differing structures. In Gomorrah, Gennaro Savastano, a mean, over-ambitious oddball, will stop at nothing to realize his determined quest to replace his father as the top kingpin, even if he has to have him killed. “Genny” is not good looking or gracious. He does not dress well, is inarticulate, and moves awkwardly. Spadino Anacleti, a member of the gypsy clan in Suburra, sports the exact same peculiar hairstyle as Genny. Spadino is fun-seeking, has great dance moves, and even shows an inclination for the romantic. Genny is a monster with whom the viewer cannot possibly find a way to relate. Spadino, a child who is transitioning to young-adulthood, struggles with his sexuality, engaging the audience who wants to see him succeed as he finds his true self. What both characters have in common is that they come from families with the kitschiest of tastes; perhaps this explains their choice of haircuts. Both live within well-guarded walled compounds.

As any Italian mafia portrayal would dictate, females in both series are clad in tasteless clothing, including furry collars and abundant leopard print. In Suburra, however, female characters are shown as having the “requisite” sensitive side that would make males in the audience feel more at ease. In Gomorrah, the leading females are as driven and heartless as the men. In Suburra, females reach their goals through seduction; in Gomorrah, they rule without having to resort to gender-based qualities. When it comes to sex scenes, Suburra has plenty of them. The series opens with an orgy and has multiple sex scenes throughout its ten-episode arc. But after the initial shock, one distinguishes the scenes as having been dreamed up by a repressed and overactive adolescent male mind. In Gomorrah, there is no sex; the characters’ lives cannot afford such commodity. Its characters’ connections are more primal than carnality.

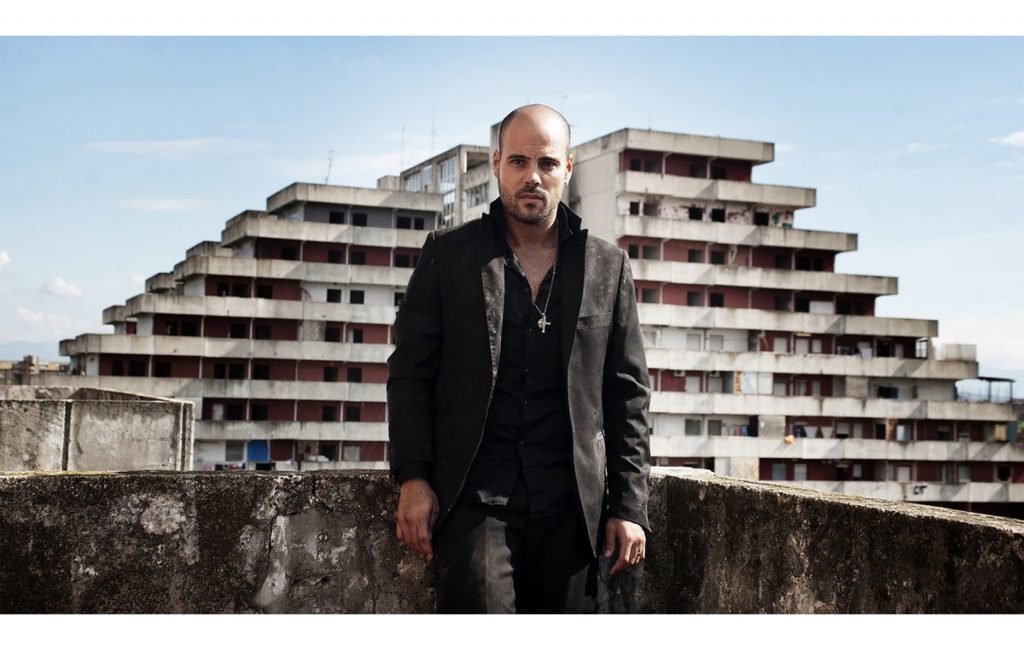

In Gomorrah, where the characters are at their most primitive, the church, which appears in understated tone, is respected and feared. In Suburra, there is expressed disdain for the Vatican. In Gomorrah, all vehicles are European; in Suburra, the bad guys drive American. In the former, Ciro di Marzio – it took me almost the entire first season to understand he was the main character – looks and acts 100% Neapolitan; in the latter, his counterpart, Aureliano Adami – who in the movie version appears like a euro-skinhead – looks Angelino in the TV series, even when he is not driving his American-made Jeep. In Suburra, Aureliano compassionately rescues the dog of one of his victims. In Gomorrah, Ciro smothers his wife to death.

Both series allude to the construction industry, and while watching I was reminded of an old employer who once who told me, “If you want to see the reach of the mafia in any country, look no further than at their construction industry.” – Heavy!

Suburra’s entire plot gravitates around the mafia seeking control of Ostia, the coastal town west of Rome, to build a new port and turn it into “the new Las Vegas”. One of the characters, perhaps the only decent one, is a builder. In his office, we can see architectural models and drawings. In one of Gomorrah’s many underlying plots, Genny marries the daughter of a construction magnate who wants to bring him into the family business, one that (in addition to being murky) seems “cleaner” than those of the Neapolitan mafia. Another character in Gomorrah, Salvatore Conte, hides his drug business behind a real estate development empire in Barcelona.

Architecture is a critical character in both series and plays the role of the “good guy” or “bad guy”, depending on which series you’re watching. In Suburra, architecture appears as a character in the form of an abandoned seaside restaurant belonging to Aureliano who wants to restore it to its former glory when his long-deceased mother ran it. This endeavor is likely to be interpreted as a bonding crusade between Aureliano and his mother, whom he lost as a baby. The old wooden structure is picturesque, and although now in disrepair, the many coats of brightly colored paint give witness of having been cared for. In a way, one could also presume that the building wants to save Aureliano from a life of immorality, much like a good mother would.

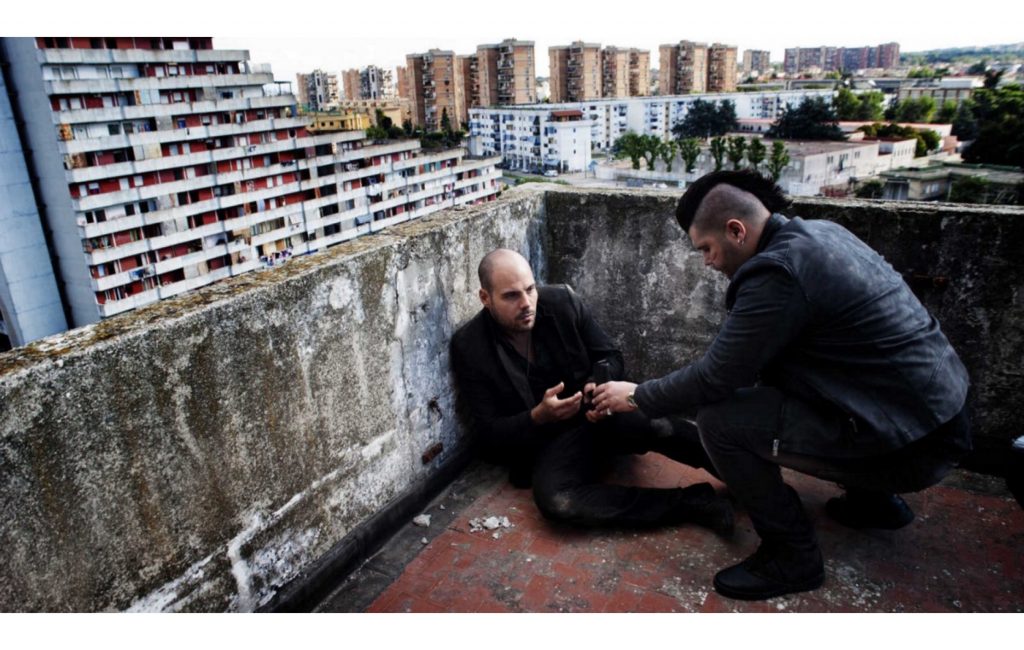

In Gomorrah, Le Vele di Scampia, the derelict set of social housing buildings where most of the action takes place, shows up as a principal character on the series promotional posters where architecture plays a defining role. While Aureliano’s seaside kiosk “smiles” in hopes of being restored, of being redeemed, of saving his owner, Le Vele is at guilt. The somber housing complex knows its architecture is the root of all social evil. That it is the cause of their indignity and moral decay. And for that, it suffers; it groans, it even constantly weeps (water drips from everywhere). Opposite to Aureliano’s wooden shack, the buildings of Le Vele di Scampia scream to the viewer that they’ve never been cared for. That their existence has been a downward spiral from the onset. That they know of their complicity in the bad that dwells in their guts.

Abandoned industrial sites and port settings constantly appear as backdrops in both series. The gangsters in Suburra often meet under freeways or in impressive skeleton-like concrete structures such as those in the failed and abandoned Santiago Calatrava project, Sports City. Their white-collar counterparts do so in glorious Roman sites which include the Palazzo Senatorio and other monumental and institutional structures. In Gomorrah, there are no white-collar criminals outside of one or two very minor characters, and all meetings happen in the open, the majority of them on terraces or open hallways of Le Vele.

I enjoyed and recommend both series. For those looking for an easier to digest, faster-paced crime story, Suburra is the choice. But for those who can tolerate few words and can stomach primitive European mafia gore and ruthless violence – both physical and psychological – Gomorrah is the option. I’ve always been strangely attracted to the superstructures of Italian social housing, from Futurism through Modernism and until the 1960s and 1970s, when Le Vele di Scampia were completed. I am particularly fascinated with the counterpoint between the positive impact they continue to have from an architectural design standpoint and the diametrically opposed adverse effect they had over the lives of those they were originally intended to help. Given the option, I choose Gomorrah.